When Clint Boston goes for a run at dusk in a densely wooded riparian corridor at Bear Creek Lake Park, a creek setting that is cherished by local nature lovers, he’ll often notice owls coming out to accompany him.

“I’ve had so many amazing owl encounters,” Boston said. “They are flying right by you as you’re running, almost as excited to see you as you are them. I’ll be running, and off to the left or the right, an owl is flying right next to you.”

Roy Johnson, who lives nearby, refers to the riparian corridor along Bear Creek as “the enchanted forest.” Visitors say the sound of rushing water flowing over small rapids is soothing, as is the rustling of leaves in warmer months.

But a mile of that riparian habitat along Bear Creek, just upstream from Bear Creek Lake, may be threatened. The lake was created by a dam constructed in 1977 as a flood control project, but now the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is conducting a feasibility study to determine whether the reservoir should be “reallocated,” meaning repurposed, to store more water for Colorado’s rapidly growing population.

Boston calls the potential threat “incredibly scary” for park users. If the project were to be built, the water level of Bear Creek Lake could rise more than 50 feet and the area of the lake could increase more than five times its current size.

“For me, the scary part is the loss of some amazing trails,” said Boston, who coaches the Green Mountain High School cross country team and often uses the park for training his runners. “You really have thousands of options to run in one park, which is fairly unique. That’s the scary part, the sheer number of trails that would be lost.”

The Army Corps of Engineers owns the land and leases it to Lakewood for recreational purposes. The city has posted informational signs in the park making visitors aware of what is being considered, and it has a web page devoted to the reservoir expansion proposal, including a spreadsheet outlining what features of the park could be lost. At three of the five potential water levels being considered, the city concedes that the expansion of the reservoir could “result in change to (the) character of park recreation from land-based to water-based.”

“The beauty of living in Lakewood is that we have open space that we can get to, relatively close,” Johnson said. “And it is not just marginally nice, it’s actually beautiful. To put more water in there and eliminate so much of what it has to offer would be a shame.”

For mountain biking, the park’s relatively gentle trails are perfect for beginning riders and those who aren’t looking for white-knuckle technical terrain. If the Bear Creek project is approved, the Beti Bike Bash — the largest all-women mountain biking event in the U.S., which typically attracts more than 400 riders — might have to move. That event exists to expose more women to the sport, and at last year’s race, three-quarters of the participants were beginners, according to race director Natalie Raborn.

“I don’t think not being challenging (for mountain biking) is a weakness of Bear Creek; I think it’s a positive,” Raborn said. “Having that go away would be bad, because the race is going to be at risk. We’ll look around for somewhere else, but one of the reasons it’s so successful is that it’s at a place where women can come out and ride a race without fear that it’s above their technical ability. That’s unique to Bear Creek Lake Park.”

Officials can’t say when the expansion project would begin, if it were approved. The current feasibility study, which began last fall, is scheduled to conclude in 2024.

“We are only examining whether or not we could store additional water behind the dam,” said Erik Skeie, special projects coordinator for the Colorado Water Conservation Board. “We don’t even know if it’s going to be possible. It’s looking at, ‘OK, if we were able to store additional water, can we still have this recreational facility? Can we move trails? Is it still going to offer the same experience? Are we going to be able to mitigate for environmental impacts properly?’ All of that is put into this feasibility study.”

There are multiple beaver dams on Bear Creek and Turkey Creek, along with lots of other wildlife. Those habitats could be lost.

“With each dam, there can be multiple generations of beaver living there,” said Drew Sprafke, who is Lakewood’s open space supervisor as well as a ranger and naturalist at the park. “We have a lot of nesting birds, both raptors and nesting songbirds. We have nesting red-tailed hawks most years. It’s a corridor for coyotes, and occasionally for black bears.”

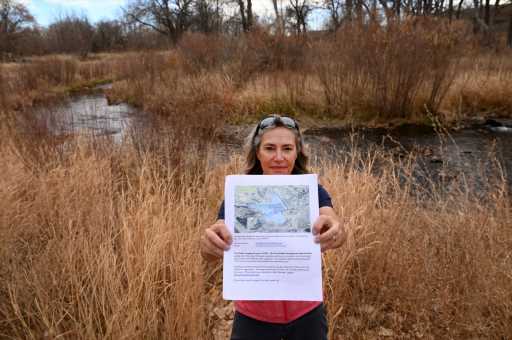

On a beautiful Friday afternoon between winter storms, project opponent Katie Gill paused to admire one of her favorite spots in the riparian area of the park, which would be 50 feet underwater if the maximum water storage increase occurred. It’s one of the reasons she founded an advocacy group called Save Bear Creek Lake Park.

“What’s so great about this section is the creek; it’s a living river,” said Gill, whose group distributes yard signs and uses social media to get their message out. “This is a section of the park where there are lots of birds, and the trees on both sides of the creek, when they’re filled with leaves, you can’t see out to the roads. You’re in this corridor, and the (sounds) of the moving water and the rustling leaves, the birds chirping, it takes over your sensory experience.”

After a public meeting hosted by the Army Corps and the Colorado Water Conservation Board last October, Skeie reached out to Gill and asked her to show him the park’s assets from her point of view.

“To be there and talk to someone who uses the park every day was great for my understanding,” Skeie said. “My better understanding is going to help me advocate for that recreational impact in the study.”

Gill and others who are alarmed by the potential impacts of the project concede Colorado will need more water storage capacity in the future, but they’re hoping it can be achieved without ruining the park they love. Liam Hopkins, a junior at Green Mountain High School, joined Save Bear Creek Lake Park and will speak for the group at a Lakewood City Council meeting on March 28.

“Almost every trail that I run or bike, or almost every place I go to look at animals, would be completely destroyed” if the maximum water reallocation occurred, Hopkins said. “The best parts of the park are in that riparian corridor. My ability to use the park would be completely erased.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, The Adventurist, to get outdoors news sent straight to your inbox.

Source: Read Full Article