In March 2020, much like the rest of the world, Kenya shut its borders to international travelers, bringing its billion-dollar tourism industry to a screeching halt. Now, more than a year later, the African nation is taking stock of its most precious attraction: its animals.

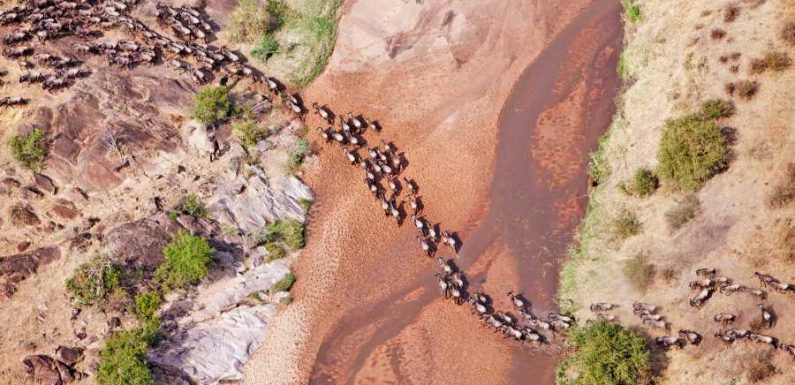

In May, scientists, rangers, and an army of volunteers began the arduous task of counting every single wild animal in the nation as part of its first wildlife census. That means accounting for every elephant, every giraffe, and every hippo across 58 national parks.

According to Reuters, leaders will run the census program through July both from the land and by air via helicopters. It will also serve as a stepping-off point for understanding just how the country can protect its more than 1,000 native species, some of which have seen rather terrifying population drops in recent years, as well as how leaders can better disperse funding for conservation efforts. This is why, Reuters reported, the team will focus much of their efforts on counting rare and endangered species like the pangolin and the Sable antelope, of which just 100 remain in the wild.

“We know there are major gaps,” Winnie Kiiru, acting chairperson of the Kenya Wildlife Research Training Institute, shared with Reuters about the sparse information they have on current wildlife statistics. “We probably don’t know much about what is going on in Northern Kenya.”

Load Error

There is also some good news going into the count. As CNN reported, Kenya had a mini elephant baby boom over the pandemic, with a reported 200 new babies entering the world. Najib Balala, Kenya’s tourism minister, called them the nation’s “covid gifts.”

As for what may be causing the decline, Reuters noted a slew of issues including expanding human settlements in the region, poaching, and of course, climate change.

Though counting animals may seem like a more fun task than most, the pandemic could make it more difficult for the experts to find each one. Animals, the experts noted to CNN, have changed their migration patterns over the last year as there were no people around to stop them.

“We will establish where these wildlife are in time and space,” Dr. Patrick Omondi, acting director of biodiversity, research, and planning at KWS, shared with CNN. “We have seen wildlife going into spaces they have not been in 50 years.”

Source: Read Full Article