Tom Hornbein forever will be known for his bold first ascent of Mount Everest’s West Ridge as part of the first American expedition on the world’s tallest mountain in 1963, an audacious achievement which left his mark on the mountain forever. A section high on the route has been known ever since as the Hornbein Couloir.

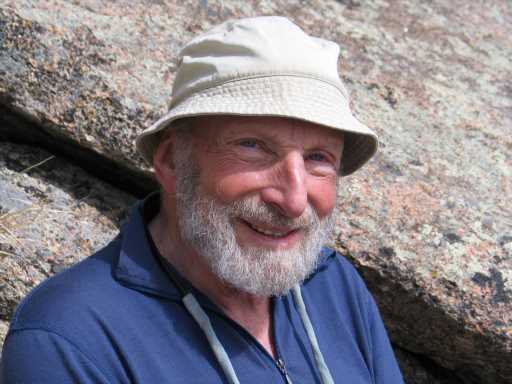

Hornbein, who died in Estes Park on Saturday at 92, earned his fame by what he and climbing partner Willi Unsoeld did on Everest 60 years ago this month, which included the first traverse across the mountain’s summit and an overnight bivouac while descending the Southeast Ridge at 28,000 feet. Yet he is being remembered by those in the mountaineering community for his humility as much as his epic Everest story.

“What he did on the West Ridge was insane,” said Jake Norton of Evergreen, who has summitted Everest three times. “It changed Himalayan mountaineering unalterably in massive ways. It was so visionary for the time, and yet what I cherished most about Tom was that you could be in a room with him for hours and he’d never bring up Everest or the West Ridge. You had to pull the strings of Everest and mountaineering out of him. He was humility defined.”

Having reached the summit via the West Ridge at 6:15 p.m., Hornbein and Unsoeld descended via the Southeast Ridge, which other members of the expedition had used to summit before them. They had to stop when it got dark and hunkered down for the night.

“That climb required a lot of heart and soul,” said David Breashears, an Everest icon who grew up in Denver and summitted the mountain five times. “To do something like that back then was utterly unheard-of. It took such a leap of imagination. It was getting late, and they had to make a decision because they had to descend a route they’d never climbed. It was a daring thing. It was heroic. It almost brings tears to my eyes to think of that kind gentleman and his contribution to mountaineering.”

Hornbein was born in St. Louis but fell in love with mountains when his parents sent him to summer camp in Estes Park when he was 13. He went to the University of Colorado to study geology but cut classes frequently to go climbing. He later studied medicine and became an anesthesiologist, spending much of his professional life at the University of Washington. He moved to Estes Park in 2006.

“This is where I really cut my teeth and learned how to climb,” Hornbein said in a Denver Post interview at his Estes Park home in 2011. “Those winter ascents on Longs (Peak), the winter camping, were really my training ground. It wasn’t just Longs, but it was the centerpiece of the playground that I learned on.”

The objectives of the 1963 American Everest expedition were hotly debated within the team. Hornbein and others argued vociferously that they should attempt the unclimbed West Ridge, while others wanted to climb the Southeast Ridge via the South Col that was pioneered by Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay 10 years earlier. The West Ridge contingent believed making a first ascent would be a greater achievement, but the South Col supporters were adamant, believing it was imperative that the first American Everest expedition succeed even if it was by a route previously climbed.

Ultimately there was a compromise. After Jim Whittaker and Sherpa Nawang Gombu summitted by the Southeast Ridge, Hornbein and Unsoeld got the go-ahead to pursue their dream on the West Ridge. Hornbein told his story in a book — Everest: The West Ridge — which is one of the classics in mountaineering literature.

“Not to take anything away from Jim Whittaker and Gombu, but to me, if there was a seminal American ascent of Everest, it was the West Ridge,” Norton said. “It got largely overshadowed by the first American ascent of the mountain up the Southeast Ridge. I just always felt their story was so much more important. It kind of got relegated to the dusty pages of history, but Himalayan mountaineering in its current iteration couldn’t have existed without Tom and Willi pushing the envelope as far as they did in ’63. It was just such a stunning story.”

Hornbein continued to climb during his golden years in Estes Park, thrilled to be back where it all began. He climbed the famous vertical Diamond on the east face of Longs Peak, one of the classic faces in American mountaineering, when he was almost 65.

“It’s adventure,” Hornbein said in the 2011 visit. “It just comes in all sizes and all kinds of packages. For me here, just wandering by myself is wondrous, and when one of these young guys will take me out on the edge of what I’m capable of — and maybe a little beyond — I get the same charge out of that as all the rest.”

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter, The Adventurist, to get outdoors news sent straight to your inbox.

Source: Read Full Article