The answer to your prairies: Canada’s province of Manitoba is a long way away – but offers thrilling wildlife and a rich culture

- Doug McKinlay finds that visiting Manitoba is a ‘true outback adventure’

- During his stay at Gangler’s North Seal River Lodge he sees the Northern Lights

- READ MORE: Why Saint Lucia is the best island in the Caribbean

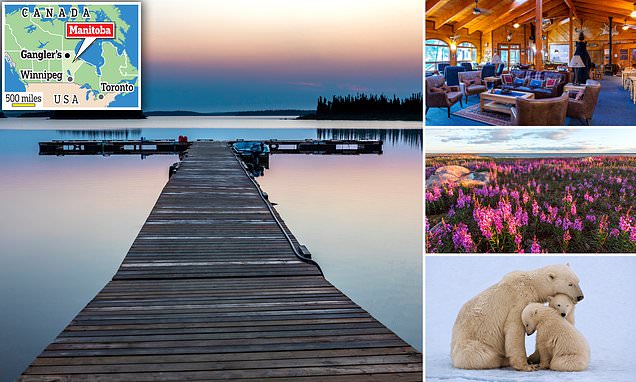

Dawn has yet to break, but across the flat horizon a vague orange glow begins to edge out the darkness covering the still waters of Egenolf Lake.

In the receding gloom, a jetty slowly becomes visible, at the end of which sits a 1950s De Havilland Beaver, the legendary floatplane of the country’s north. It’s my first morning in sub-arctic Manitoba, one of Canada’s three huge prairie provinces.

As the sun rises above the pristine spruce forest of a near-shore island, the staff and guests of Gangler’s North Seal River Lodge, my base of operations for the next four days, begin their morning routine.

I’m just shy of the border between Manitoba and Nunavut, the fabled territory North of 60 (the area of Canada lying north of a latitude of 60 degrees) and home to the Inuit people.

The current BBC series Race Across The World has sparked interest in Canada, but this fascinatingly remote part of the country seems to have missed the cut. Perhaps simply because it’s a long, long way away. From the UK, it’s a flight to Toronto, Ontario, then connecting onto Winnipeg, Manitoba’s capital. A night in ‘The Peg’ helps dislodge some travel fatigue before boarding a De Havilland Dash 8, the Gangler’s Lodge private aircraft, at 5.30am for the final three hours to the far northern reaches of the province.

Light fantastic: Doug McKinlay travels to Canada’s sub-arctic Manitoba province, where he stays at Gangler’s North Seal River Lodge overlooking Egenolf Lake (pictured)

As cumbersome as getting here might be, this is a true outback adventure. Gangler’s is a five-star fly-in/fly-out only facility; the nearest road is 180 miles to the south. The lodge’s holdings cover an immense expanse of nearly 19,000 sq km of untouched wilderness, a spider’s web of 12 river systems and more than 100 lakes merging with one of Canada’s great rivers, the North Seal.

From its inception in 1985 by Chicago-born fisherman and outfitter Ken Gangler and his dad Wayne, Gangler’s Lodge was dedicated to running trophy fishing and hunting trips to well-heeled travellers.

The vast number of northern pike, arctic grayling and lake trout that drew visitors made it (almost) like shooting fish in a barrel. But a few years ago, things began to change. Ken looked at the lodge’s future from a different perspective.

He doesn’t hunt any more and sees Gangler’s morphing into an ecotourist destination that focuses on educating visitors on nature and environmental sustainability and celebrating the local culture of the First Nations people, the Dene and the Cree, just two of the more than 650 recognised indigenous groups in Canada.

‘For sure this place is a fisherman’s dream, but it’s more than that,’ he says. ‘In the coming years, my goal is to make the lodge and its surroundings more open to people who don’t hunt or fish, people who have a real thirst for knowledge about Canada’s north. It’s such a fantastic location and I want to show that off to as many people as I can.’

While the Caribou herds can rest easy, wildlife viewing, mountain biking, kayaking and canoeing will take centre stage.

The lodge is a large log cabin structure with a high-pitched roof. Inside, there’s a cosy bar next to a grand inglenook-style fireplace, with a pool table off to one corner and shelves of board games and books. The centre of the room is all sofas and squishy chairs while large floor-to-ceiling windows let the northern light stream in.

About 20 metres from the lodge, a well-used fire pit surrounded by chunky Adirondack chairs is the perfect setting for campfire chats and Aurora Borealis spotting.

Gangler’s Lodge is an ecotourist destination that focuses on educating visitors on nature and environmental sustainability

Authentic: The central space at Gangler’s Lodge has large windows to ‘let the northern light stream in’

Doug says Manitoba is ‘cumbersome’ to get to from the UK

Accompanying me are Americans Mike Schibel and Christine Peterson. Like me, they have a real desire to dig deep into this environment. ‘Gangler’s is in the middle of this amazing natural resource: wildlife, Northern Lights, First Nations cultures and too many lakes to count,’ says Christine.

‘And the way Ken is shifting his focus to clientele who are not into hunting and fishing is so long-sighted, it has to be the way forward.’

After a quick coffee and pastry, we head to the jetty to meet Brian Kotak, Gangler’s resident biologist. He’s exactly what I expect from a wilderness biologist: thick-framed glasses, salt and pepper hair, a goofy sense of humour. He may not be able to leap tall buildings in a single bound, but his superpower is intimately knowing all the region’s flora and fauna, as well as the province’s geological and cultural history.

Our aluminium-hulled boat skims across mirror-flat Egenolf Lake to Robertson Esker, a long sand and gravel ridge that towers 140 metres above the surrounding country. It was formed during the last Ice Age by meltwater channels on and in glaciers as the ice retreated 8,000 years ago.

Relatively clear of trees and with a high windswept vantage point, Eskers have for millennia been important causeways for wildlife and the First Nations of the region. Fresh animal tracks embedded in the sand show just how busy this tundra superhighway can get.

The great outdoors: Doug describes Manitoba as ‘one of Canada’s last great wildernesses’

‘Welcome to the Great Canadian Poo Tour,’ Brian jests, as he kicks over a week-old pile of wolf scat.

Standing at the top of Robertson Esker, he holds court, bringing to life the geologic history of these sandy hills and what part they play in the region’s peoples, past and present. He can belt out a very convincing moose call, too.

The greater topography beyond the Esker levels out into low undulating hills, overlaid by stands of stunted black spruce, jack pine and birch trees of the boreal forest. The ground is covered by a thick spongy blanket of yellow lichen, winter food for migrating caribou herds.

Modern-day hikers can snack on lingonberries, blueberries, cloudberries and raspberries, reveals Doug

There is an abundance of lingonberries, blueberries, cloudberries and raspberries — all snacks for any passing polar or black bears, bison or even modern-day hikers. This is the Land of the Little Sticks, a Cree and Dene First Nations description of the forests that are their ancestral home.

I didn’t come for the fishing but it’s almost impossible to ignore. ‘There is an unimaginable population of northern pike in these lakes,’ says Stephen Snipper, 79, an American guest at the lodge. ‘You could catch them for ever without any meaningful skills or any impact on the numbers.’

Two members of our group are tasked with catching four pike, which our Cree and Dene guides then use to make what’s called ‘shore lunch’.

Doug says that polar bears are part of the province’s diverse wildlife

Big beasts: Black bears and bison roam the region, Doug reveals

TRAVEL FACTS

Canada As You Like It offers packages to Gangler’s Sub-Arctic from £5,420 for five nights, including flights from the UK, one night at Winnipeg Airport hotel, return flight to Gangler’s North Seal River Lodge, four nights at the lodge on full board, four days guided nature, history, wildlife, photography and Northern Lights tours (canadaasyoulikeit.com/ganglersnorthsealwildernesslodge, or email: [email protected]).

Brothers Travis and Tyler Merasty, of the Cree Nation, get started prepping the fish and potatoes while Simon Antsanen, of the Dene, tends to the fire and pops open tins of baked beans, cooked in the can over the open fire.

Sitting on a pristine kilometre-long sandy beach, it’s one of those rare moments when everything comes together: good food, interesting company, beautiful light.

But my day is not over, we race back to the lodge as the afternoon creeps on. Nearby, at the side of the lodge’s 1,700 m-long landing strip, sits a small two-person hide. A wolf and her cubs have been seen near the runway in recent days and I want to try my luck at catching sight of her. I know it’s a good spot; pressed into the sand next to the thin nylon structure are numerous wolf tracks, some old and some new.

I have barely enough time to right my rickety stool before she comes loping across the airstrip. There are no cubs this time, but she is impressive, large and healthy, with a natural curiosity that forces her to stop in front of me. But it’s all over in a flash. She stops, she looks and then she’s gone.

As the sky fades to night and dinner is over, the firepit is lit and we all wait to see if Mother Nature’s lightshow will make an appearance. We wait and we wait. Slowly, the group begins to thin, first to go is Christine followed by Mike, then Ken; the day’s adventure is taking its toll.

By 1am I’m on my own and the fire is all but out. Then, ever so slowly, the sky reveals the Aurora. It dances across the horizon in curtains of green and red, reflecting off the flat waters of the lake. For a good hour it’s just me and the Northern Lights, a superb ending to a fascinating experience in one of Canada’s last great wildernesses.

Source: Read Full Article