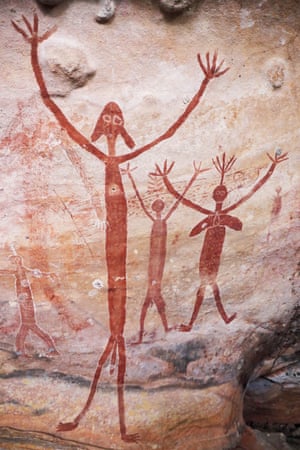

The area around Laura, 300 kilometres north of Cairns, on Cape York peninsula, is also known as Quinkan country, in recognition of spirits whose enigmatic forms are boldly painted on these walls.

Indigenous guides can take you to selected places where these figures are seen, sometimes among animals including ibis, dingoes, flying foxes, snakes and kangaroos, or plants like the edible native yam. Often shown lifesize, these beautiful images are created using vibrant ochre, mostly in shades of yellow, red, brown and white.

Animals now extinct, such as the diprotodon or giant wombat, are said to be depicted here. The guides share their rich stories and, if the season is right, explain which fruit to pluck from which tree. The technique and approach of local painters is distinct to others further afield; this is evident in the way they shape solid blocks of colour or simple lines, both fine and broad, sometimes strongly patterned. In some areas, the edges of an animal’s body give shape to an image as it was held up to the rock for stencilling with ochre.

Despite the significance and irreplaceable cultural wealth of these sites, their protection is inadequate according to the Australian Rock Art Research Association. National Heritage listing in 2018 means the federal government is now also responsible for protection.

Across the country, Indigenous people and landholders have developed respectful partnerships, ensuring sites are known, documented and cared for.

Tragically, many others do the opposite and actively destroy these riches. In a whim of opinion and flash of time, complex works that survived thousands of years disappear. For some, it is fear fed by rumours – that “they can take your land if there’s evidence of sites”. For others, it is wilful destruction born of two centuries of a partial and surreal education. Australia has a lot to celebrate and this region presents excellent opportunities.

One hundred kilometres east of Laura, heading towards the coast, country that gradually changes is suddenly, startlingly different. Black forms loom up among vibrant green as though defying every logical explanation of power and volume, not simply due to physical size. Oxidisation and algae have darkened Kalkajaka (also known as Black Mountain). The blackened boulders rest in massive gatherings, protecting the solid core that lies beneath. This is an important place for Kuku Yalanji people.

In conversation with an Elder, a comment is coupled with a question: “Strong place that one, eh?” The response is quick and simple: “Yuwu, we don’t go there. Too strong. Some people who don’t listen go. And trouble comes.” Enough individuals and groups, along with their animals, have vanished from Kalkajaka: logic tells us to look at the tumbled maze of boulders to explain the disappearances.

Another view is that this is one of the sacred places across the country recognised by the old people as a vital gathering of energy for replenishing the land. Some say there are places where the earth wants to be left alone, without the presence of humans. To ignore the needs of the earth to such a degree is dangerous. These boulders also provide refuge to three known endemic species: the Black Mountain skink, the Black Mountain boulderfrog and the Black Mountain gecko are not known to live elsewhere.

Less than 30km north of Kalkajaka along the highway that cuts its north-west edge, is Gangaarr, the Cooktown area. Situated between mouths of two rivers and cradled by coastal hills, this area holds significant history. Long honoured by the Guugu Yimithirr and surrounding groups as a haven where no human blood was to fall, Gangaarr was a place for gathering, birthing and resolving disputes. A great stroke of luck for the explorer James Cook. In June 1770 he arrived with his crew when their ship, the Endeavour, was in dire need of repair. They had spent arduous hours pumping water to keep her afloat at the edge of the reef they’d struck and were relieved to come across Waalumbaal Birri. This river is now commonly known as the Endeavour.

Australia’s top eight Indigenous travel destinations | Marcia Langton

The Guugu Yimithirr were not expecting such a significant intrusion into their world. In his diaries, Cook described the exchanges and interactions as amicable and often friendly, despite language and cultural differences.

Here too Cook recorded in his diary their first-ever sighting of an Australian macropod, though there is still conjecture about which of the many species they saw. Perhaps an eastern grey kangaroo or agile wallaby, perhaps a whiptail. Guugu Yimithirr speakers confirm that today’s generic term for a kangaroo originates from their language, where gangurru describes an “old man eastern grey kangaroo”. Some people suggest gangurru means “go away”. This is one example of many where translation across cultures can easily go awry, and the need to turn to Elders who hold knowledge is necessary.

Cooktown was established in this area in 1873 as a supply port for the Palmer River goldfields, which brought immense bloodshed, disease and disruption to this land and its people. The industry boomed for a decade or so in which time the town reputedly had more than 60 pub licences and as many brothels to feed the lifestyles of recent arrivals. Riches of the time are still visible today, and you can explore the complex history in places like the James Cook Museum, which is working with local Elders to present a more balanced view. Grassy Hill and Mount Cook offer tremendous views of Guugu Yimithirr country. Hills slope and meet the sea, the river turns among them, offering another opportunity to better imagine those early days and how they can shape today.

As the sea stretches out, reefs pattern the blue and mingle with more than 900 islands. Management of the area is shaped in part by the knowledge and leadership of traditional custodians whose cultural responsibilities ensure healthy ecosystems. More than 70 distinct groups hold ongoing and diverse connection to the Reef that stretches 2,000km from the Torres Strait islands. This provides incredible opportunities to honour the wealth of knowledge, as seen in the work of Indigenous rangers across the country.

The Bloomfield Track, which connects Cooktown and Cape Tribulation is touted as one of Australia’s greatest four-wheel drive tracks, but is also highly contentious, known for significant protests against its construction in the 1980s.

The logging industry, land developers and Queensland government strongly contested that there would be impacts on rare ecosystems of the Wet Tropics brought by increased intrusion. Vested interests moved the argument this way and that, increasing national and international attention. Despite strong government opposition, requirements for World Heritage listing were investigated and, finally, in 1988 the Wet Tropics were inscribed on to the World Heritage list.

Those of us lucky enough to travel through these lush hills can only begin to imagine how life, and therefore the land, would be if current management more closely aligned to that of the country’s First People. Priorities continue to shift between Indigenous knowledge and practices, commercial activity, biodiversity, tourism and other considerations. Many of these could complement each other if we choose to respect long-known truths.

Indigenous cultural experiences, tours and relevant organisations

In or near Laura

Quinkan Regional Cultural Centre

The centre’s informative display provides information regarding the local ancient culture and more recent changes. Book your tours here – be sure to ask if one of the Indigenous guides is available. The community takes the care of the incredible paintings very seriously and asks visitors to do the same. Visitor numbers need to be controlled for the long-term preservation of this place so if at any time you are told you cannot visit, take joy in the knowledge that your absence is an important part of active care for country.

Rinyirru (Lakefield) national park

This is a seasonally accessible area and is usually closed in the wet season, so please check before you go. High rainfall can make roads impassable. Ignoring road closure signs may compromise the safety of others and likely damage the roads for some time to come. There are many small tracks off the main dirt road and respectful travel is necessary. There are areas where you will be asked not to enter due to cultural significance, so please respect the people and country.

Split Rock

If for some reason you cannot meet one of the local tour guides working through the Quinkan Regional Cultural Centre for a guided tour, you can visit Split Rock on your own. The uphill walk leads you past rock art galleries of varying complexity and story. Please always respect the signs, do not venture beyond, and enjoy pondering the ancient layers and local figures. Please be sure to carry cash and pay the very modest fee – the community appreciates it when people show good will.

Laura Dance festival

This unique celebration is held on ancient ceremony grounds where many groups of the region have gathered for countless generations. Check the festival’s website for the latest updates.

In or near Gangaarr (Cooktown)

Kuku Bulkaway Indigenous Art Gallery

You can enjoy the work of local artists whose inspiration comes from their connection to the land and sea that surrounds them. They share stories of plants, animals, bush foods and life in the Cape York region.

Milbi Wall

This story wall is a local icon for reconciliation. You are invited to learn rich details of Aboriginal history – from the creation of ancient rivers to recent events such as the 1967 referendum. Allow time for this complex work, as images and words of local artists set in ceramic tiles deserve attention and time.

Foreshore, Charlotte Street, 150m north of Hill Street

Mount Cook national park

Be ready for some steady uphills through diverse ecosystems offering expansive views of surrounding country. Keep a lookout for all sorts of creatures – from beautiful green tree snakes that are not always green to birds that have travelled from New Guinea. A walk begins near a small car park in Hannam Street near Boundary Street.

Grassy Hill

You can drive to the top of Grassy Hill for immense views and richly layered stories of the area’s Indigenous people and recent changes in their country. Walking up the steep road offers some informative stops and excellent opportunities to appreciate the scale and flow of the country. The Scenic Rim walk that connects Grassy Hill to Cherry Tree Bay, the Botanic Gardens and Finch Bay can be found near the lookout.

James Cook Museum

Exciting partnerships create interesting presentations at this museum, where a clear view of history supports a positive shared future.

• This is an edited extract from Loving Country by Bruce Pascoe and Vicky Shukuroglou, available now from Hardie Grant

Source: Read Full Article