In April 2017, United Express passenger David Dao, who was being bumped from a flight, was forcibly dragged up the aircraft aisle and injured after refusing to comply with orders to give up his seat.

After that infamous incident, U.S. airlines sharply reduced their use of bumping as a tool to manage inventory, opting instead to eliminate or reduce the frequency with which they oversold flights, while also choosing to open their wallets wider when necessary to make sure enough people voluntarily give up their seats on oversold flights.

More than five years later, U.S. airlines are bumping passengers three times as often as they did in 2018, according to the latest data from the DOT. The bumping rate during the first half of 2018 had dropped to barely a fifth of what it was prior to the Dao incident. Today, it has crept back up to more than 60% of what it had been before Dao.

To be sure, the overall bumping figure is still tiny. Just one in 25,000 ticket holders on the 10 largest U.S. airlines were forced to skip their scheduled flights due to an oversold flight during the first half of this year.

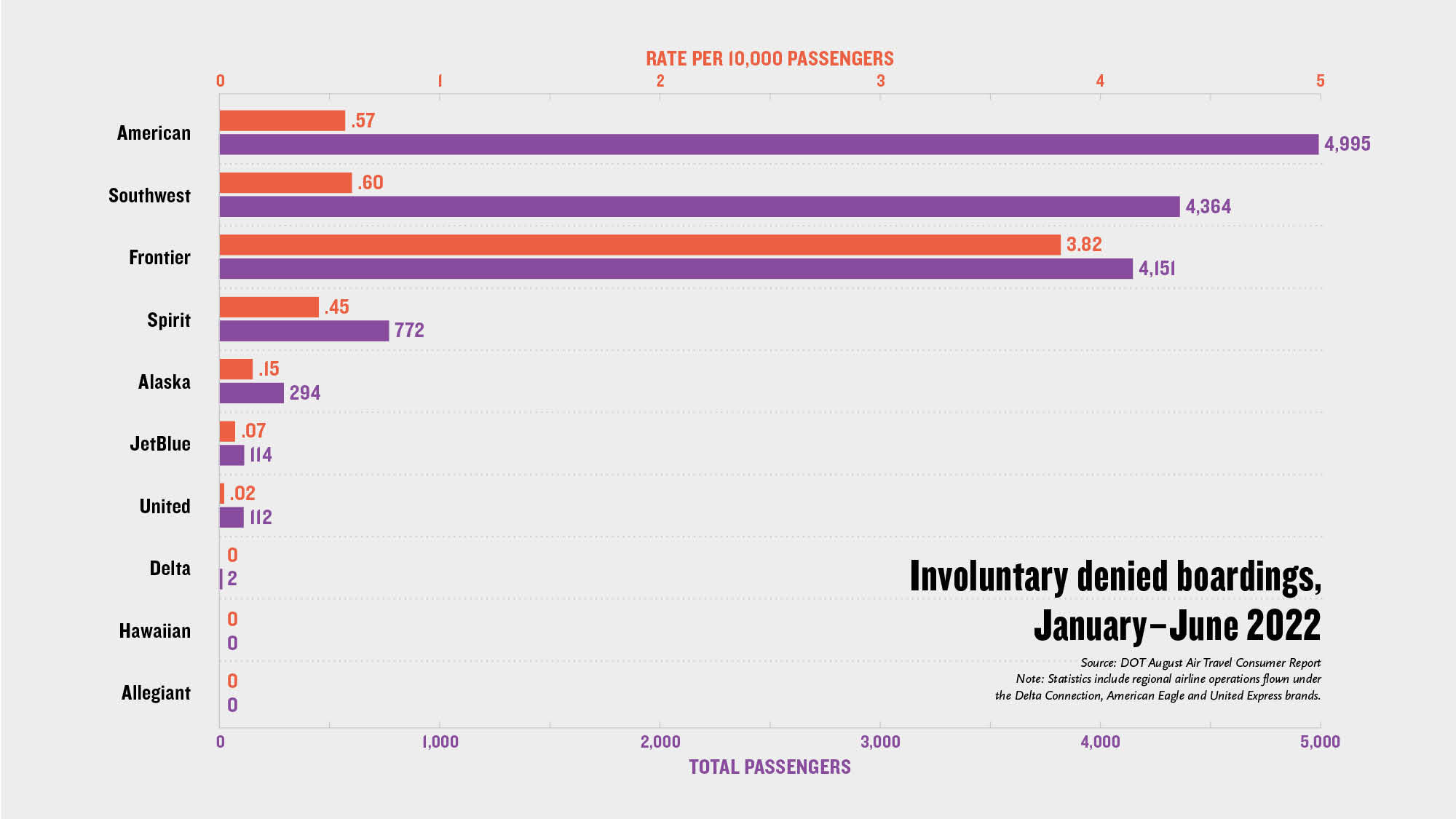

Further, the large majority of bumpings, known formally as “involuntary denied boardings,” were made by just three carriers: American, Southwest and Frontier.

Together, they accounted for 91% of the 14,805 bumpings from January through June. And while American, with 4,995 bumpings, was the most frequent perpetrator, Frontier passengers had by far the highest chance of being told they couldn’t fly. The discount carrier bumped 3.82 passengers per 10,000 during the first half of the year, more than six times the number at Southwest, which had the second-highest bumping percentage and nearly 4,400 total bumpings. (The DOT data on bumpings is self-reported by airlines.)

Conversely, Allegiant and Hawaiian didn’t bump a single passenger during the first half of this year, while Delta bumped just two people while enplaning 77.4 million passengers on its mainline and regional flights.

Airline industry analyst Bob Mann of R.W. Mann & Co. said that the airlines’ sharply different approaches are reflective of the dollar value they place on customer loyalty, and conversely, on what the long-term ramifications of bumping a passenger might be.

“If you’re a pure price customer, you’re less likely to make being bumped a brand-ending decision,” Mann said, comparing the approaches of Delta and Frontier. “If you’re a high-fare customer — a business customer — and they blow you out of a meeting, it probably is a brand-ending decision.”

Bumping is less expensive for some

Other factors also are guiding airline strategies.

Ultralow-cost carrier Allegiant explained in a statement that it doesn’t oversell flights because it typically offers low-frequency routes that it cannot easily rebook. Often, those routes fly just a couple of times per week and out of small airports that are not used by other carriers.

During the first half of the year, Allegiant had 827 voluntary denied boardings, when passengers agreed to give up their bookings in exchange for accommodations and future flight vouchers. Each of those overbookings was the result of an aircraft substitution, when a smaller plane was swapped for the larger aircraft that had been scheduled for the flight, a spokesman said.

Frontier did not respond to inquiries for this report, but along with continuing to overbook, numbers suggest the discount airline is less assiduous than other carriers in seeking out volunteers to give up their seats by choice in exchange for remuneration. During the first half of the year, Frontier bumped 4,151 passengers, while 5,986 people voluntarily surrendered their bookings, a ratio of more than two bumpings for every three volunteers the airline found.

Even American and Southwest, the other two primary bumpers this year, had far better ratios. American bumped one passenger for every 6.5 volunteers it found during the first half of the year, and Southwest bumped one passenger for every 7.7 volunteers.

DOT rules make bumping potentially less expensive for ultralow-cost carriers than for other airlines. Under the regulations, airlines must pay bumped customers four times the one-way ticket price, up to $1,550, if the bumping causes an itinerary delay exceeding two hours. For Frontier, which sells cheap base fares and then garners an especially high proportion of its revenue from add-ons such as bag fees, bumping compensation could often be less costly than finding a volunteer.

Another possibility, said Mann, is that Frontier hasn’t developed the technical processes to do a better job of finding volunteers.

“If it were my airline, I’d be looking at trying to fix that,” he said of Frontier’s bumping statistics. “That’s a pretty major black eye.”

Delta’s approach to bumping offers evidence that airlines can avoid involuntary denied boardings, even if they do utilize overbooking as a hedge against the expectation that some customers will cancel or change their travel plans. During the first half of the year, the carrier found nearly 58,000 people to voluntarily give up seats, by far the most in the U.S. industry, while bumping just two passengers.

The carrier has developed a reputation for making generous payments to volunteers when necessary. In late June, Delta reportedly offered passengers $10,000 to give up their seats on a flight from Grand Rapids, Mich., to Minneapolis.

In an interview, Delta spokesman Morgan Durrant wouldn’t confirm that report, though he did discuss the carrier’s general methodology to avoid bumping.

“We’ve got the procedures where we can get to compelling numbers where customers will volunteer,” he said. “That’s the approach.”

Explanations from Southwest and AA

For American and Southwest, numbers from the first half of this year show substantial increases in bumpings compared with four years ago. Southwest’s bumping rate of 0.6 per 10,000 passengers was more than quadruple its rate during the first half of 2018. American’s rate of 0.57 per 10,000 passengers was close to five times its 2018 rate.

In an email, Southwest said that it doesn’t overbook flights, and that all situations in which it ends up with oversold planes are a result of an aircraft substitution. Along with the increase in bumpings, the carrier had more than three times as many total oversales in the first half of this year compared to 2018. Southwest said that a jump in flight disruptions this year, caused in part by the challenging pandemic operating environment, explains both increases.

“We regret anytime we must make aircraft adjustments that might result in a customer being offered accommodation on a different flight,” Southwest said.

Unlike Southwest, American had 30% fewer oversales during the first half of this year than it had from January through June of 2018. But while American bumped one passenger for every 6.5 people who voluntarily gave up a seat during the first half of this year, the carrier bumped just one passenger for every 50 volunteers during the same period in 2018.

In an email, American noted that its involuntary denied boarding rate has varied widely over the past several years, and reached 0.73 per 10,000 during the first half of 2019 before dropping off during the pandemic.

“American aims to provide a consistent customer experience, which includes having a seat for every customer,” the carrier said. “While the chances of being denied boarding are rare, unplanned events such as weather or mechanical needs do occasionally impact flights.”

Source: Read Full Article