Jonathan Helton is a policy researcher at the Grassroot Institute of Hawaii, a nonprofit policy research organization based in Honolulu.

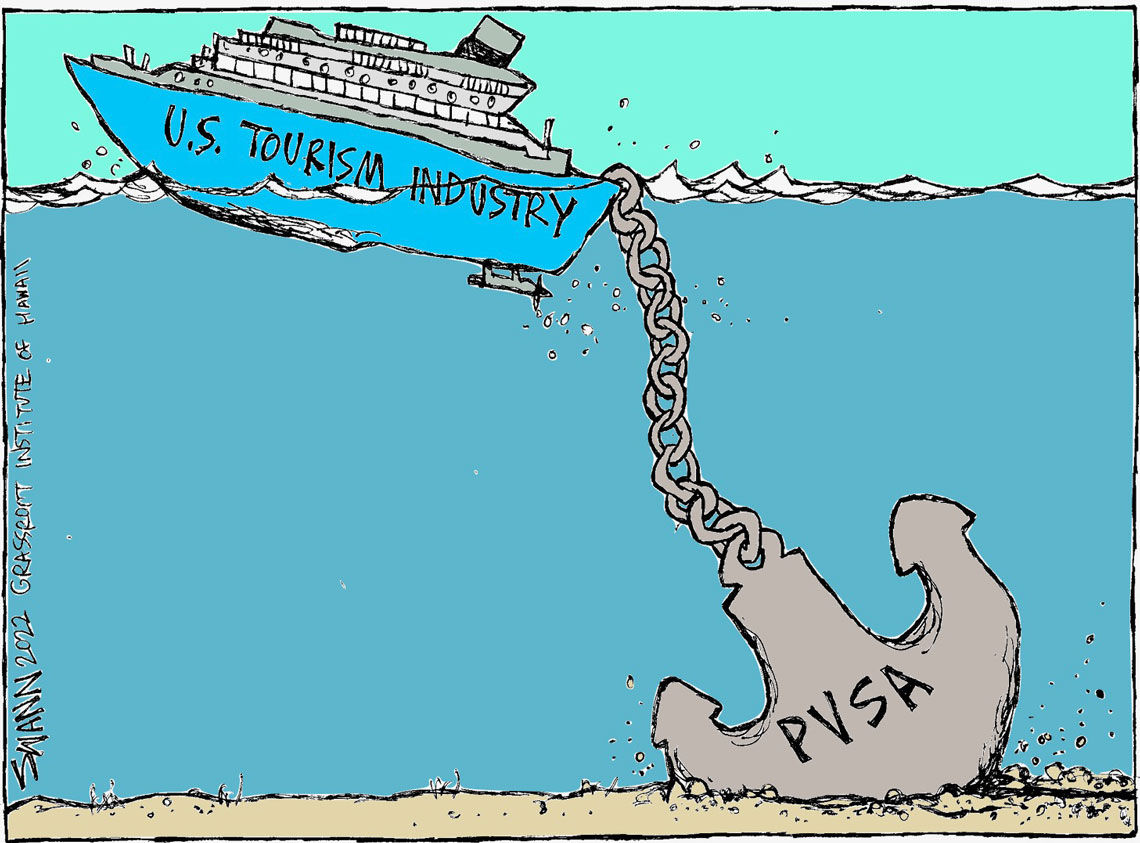

A U.S. maritime law enacted during the days before air travel is exporting American tourism dollars to countries such as Canada, Mexico and Aruba.

The 1886 Passenger Vessel Services Act does this by preventing foreign-flagged or -built ships from transporting passengers between U.S. ports, unless they make a stop in a foreign country.

For example, foreign-vessel cruises can go from San Diego to Hawaii, but only if they add Ensenada, Mexico, to the itinerary. Cruises from Seattle to Alaska typically stop in Vancouver or elsewhere in Canada, while sailings from Florida to New York usually include a detour to Aruba.

Foreign cruise vessels that start in Hawaii have been known to divert 1,000 miles south to Fanning Island, which is part of the Republic of Kiribati.

These legal exceptions enrich foreign destinations at the expense of U.S. tourism hot spots. The point of the law originally was to “protect” U.S. passenger liners from foreign competition. But those days are long gone, and the PVSA is now like a fish out of water.There is simply no large U.S. oceangoing passenger liner industry to protect anymore. As of late 2022, there is only one large U.S.-flagged cruise vessel qualified to operate under the PVSA. Ironically named the Pride of America, it was built mostly in Germany and operates under an exemption that limits its service to Hawaii.

In terms of shipbuilding, there hasn’t been a large cruise ship built in the U.S. since 1958; most large cruise vessels these days are built in Europe and Asia.

Even if U.S. shipyards could build large cruise ships, they would simply cost too much. Container ships and tankers, for example, routinely cost three to four times more to build in the U.S. than abroad.

As a result, there are no large U.S.-built cruise vessels serving the U.S. cruise market — aside from the Pride of America — and foreign ports, especially those in Canada and Mexico, are the primary beneficiaries.

Tourism dollars going elsewhere

Canada’s British Columbia, home to Vancouver and Victoria, rakes in more than $2 billion in revenue from U.S.-originated cruise ships each year, according to one estimate.

Now, Panama wants in on the action. The country announced several months ago it would be paying $100,000 to the Washington lobbying firm Potomac Partners to help change Panama’s designation under the PVSA from a “nearby foreign port” to a “distant foreign port.”

This seemingly insignificant change could be a game-changer for Panama, since most ports in North and Central America, including Panama, are considered nearby foreign ports.

Under the PVSA, U.S. cruises visiting nearby foreign ports must begin and end at the same U.S. port. In other words, a cruise to Hawaii that begins in San Diego and stops in Ensenada must end in San Diego because Ensenada is considered a nearby foreign port.

Cruises starting in the U.S. that stop at a distant foreign port — such as Oranjestad, Aruba, or Yokohama, Japan, or anywhere outside of North and Central America — may disembark their passengers at ports different from where they started.

If Panama obtained “distant” foreign port status, it could attract more cruise tourism because cruises that start in the U.S. would no longer have to return to their departure ports to disembark passengers. For example, passengers cruising from Los Angeles to Miami with a short visit in Panama would not have to return to Los Angeles aboard the same ship.

In its filing with the U.S. Department of Justice, Potomac Partners stated that a distant-port designation would “aid in Panama’s economic development.” Twenty years ago, when Panama asked U.S. Customs and Border Protection to change its status administratively, it projected that “the number of U.S. passengers visiting Panama would increase by as much as tenfold.”

Customs denied that earlier request. This time, Panama is aiming for a legislative change. Potomac Partners is hopeful it can “take necessary actions to advocate for rapid passage of this amendment to the PVSA in Congress,” according to its filing.

But Panama’s attempt to gain distant foreign port status ignores a fundamental question: Why keep the PVSA in its current form at all?

There are a handful of U.S. river cruise lines that are “protected” by the law, but why not scrap the PVSA as it applies to big ocean liners?

A world without the PVSA

Without the PVSA, cruises from Florida to Maine would be possible without an out-of-the-way sailing to Aruba. Instead, U.S. port cities such as Savannah, Ga., and Atlantic City could reap those formerly exported tourism dollars.

Cruises up and down the California coast could flourish without a mandatory night in Ensenada. People could catch a cruise ship from Oahu to Maui without the cruise line being fined $798 for violating the PVSA.

Many cruise lines might still want to include a foreign stop in their itineraries — but those stops would be determined by market demand, not an arbitrary, outdated law.

Realizing the harm of the PVSA, Sens. Mike Lee of Utah and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska have both introduced legislation to amend it. Lee is proposing that big cruise ships be exempted from the law or that the law be scrapped entirely; Murkowski’s legislation would exempt only large ocean liners headed for Alaska, so long as there are no similar U.S.-built ships that could fill the demand.

In either case, U.S. states and port communities would benefit as tourism dollars would stop flowing overseas.

Source: Read Full Article